The Mole was bewitched, entranced, fascinated. By the side of the river he trotted as one trots, when very small, by the side of a man who holds one spell-bound by exciting stories; and when tired at last, he sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea. Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows.

This is the largest mole in North America and can be found along the coast from Northern California to the southern edge of British Columbia. It is about 7.5 – 9 inches in length and weighs up to a whopping 6 ounces. You don’t get to see these animals often as they are fossorial – spending the vast majority of their time beneath the ground. But you can often spot their handiwork in the form of mounds from where they push tunnel soil to the surface and tunnels that are often close to the surface.

Scapanus, Greek skapane – a mattock, a digging tool, and townsendii for John Kirk Townsend who, with the botanist Thomas Nuttall, joined Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth’s second expedition across the Rocky Mountains in 1834. Townsend’s name is attached to a number of wildlife species he recorded during the journey. He had developed a formula he used in taxidermy preparations and arsenic was the “secret” ingredient. Unfortunately, self-exposure became an apparent problem and he died of arsenic poisoning.

Needless to say, these moles are quite adapted to their subterranean existence. Their forelimbs are modified into strong paddle-like feet that cannot be tucked under their body but extend sideways for digging. They have a keel on their sternum, or breastbone, for the attachment of the strong muscles necessary for tunneling. Their small eyes are just below the fur and likely useless and their dense, soft fur has no nap – so it can lie flat no matter which direction they are going in their tunnel. Their plush coat has over 20,000 hairs per square inch. They have a sensitive, flexible snout that is covered in tactile hairs for finding prey. They have no external ears and probably “hear” with their whole body.

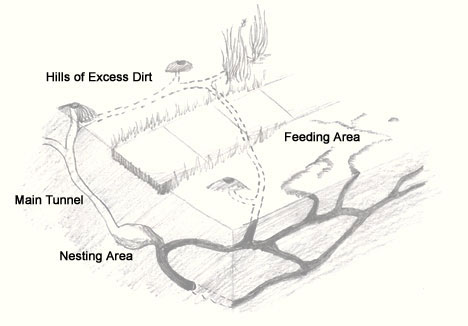

When they encounter hard soil they use one forelimb to dig while bracing themselves with the other and then alternating the pattern. Once a suitable amount of soil is loosened, the mole turns sideways or somersaults in the tight tunnel and uses its broad forefeet like a bulldozer and pushes the soil to the surface. During the spring when activity is high they can produce up to four mounds a day.

Peak breeding is thought to occur in January and early February when the female excavates an underground chamber at an elevation that is safe from seasonal water levels. Grass is used to line the chamber, which helps provide a heat source as the organic material ferments. Solar radiation also is thought to play a role as these chambers are located within 10 inches of the surface. Females produce one litter a year in March or April. The youngsters will venture out on their own in 4 to 6 weeks. Life expectancy is about three years.

Earthworms are Townsend’s mole’s main prey item, consisting of about 70% of their diet. They have long jaws filled with 44 teeth. A male will eat about 75 pounds of invertebrates a year, so they play a major ecological role in nutrient cycling and in aeration of the soil.

Here’s a brief clip of a Townsend’s mole digging away – and points for recognizing the applicable musical score at the end of the clip. Escape

I’ve come across these small animals a number of times when conducting small mammal trapping studies, but have only seen once above ground during the day. Over in Golden Gardens Park in Ballard, not far from our office here in Seattle, is a very long set of stairs that folks will use for exercise, grinding out laps on the approximately 300 ft. elevation gain. I was there with a 40 lb. pack and the headphones practicing for some up-coming mountain suffer-fest, when on my upward leg, I came across a Townsend’s mole on the cement stairway.

He was trapped in a corner of the stairs and the side walls, not able to reach the top of either. He must have just fallen from the adjoining slope. I leaned over and picked him up by the scruff of the neck (if he had one) and plopped him back on the dirt slope. It was just amazing how fast he was able to orient himself and in a couple seconds make a beeline and was gone down one of his holes. Pretty good given he can’t see much.