Es muy interesante sus metas e intereses con el almiqui (It is quite interesting your goals and interest in the (Cuban) solenodon.). —- Dr. Giraldo Alayon Garcia, Museo Nacional de Historica, La Habana, Cuba.

This is a curious creature. It is a nocturnal, fossorial, venomous, insectivorous mammal. Yes – venomous. It is one of only a handful of venomous mammals in the world. They resemble a large shrew, and in fact, had once been classified in the Order Insectovoria – the shrew Order, but as scientists are apt to do when new information arises, the Order was split several ways. The family Solenodonidae includes only two extant members – the Hispaniolan solenodon found in what is now the Dominican Republic and Haiti, and the Cuban solenodon. Marcano’s solenodon (S. marconoi) once inhabited Hispaniola but did not survive the European invasion.

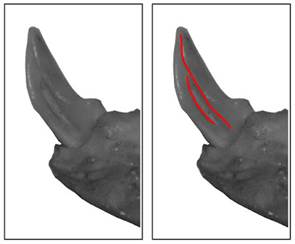

The Hispaniolan solenodon is the larger of the two extant species – it weighs between 1.3 and 2.2 lbs. and its body is 11-13 inches long with a 10 inch tail. The tail, ear tips, and snout are hairless. The fur is a rusty brown and lighter on the belly. The solenodon has a distinctive shrew-like appearance with a long, narrow, cartilaginous snout, a relatively large head, and small beady eyes. Its vision is poor and it uses its snout to probe around the ground surface in search for worms, beetles, and other invertebrates. Venom is transferred by biting via saliva, which travels along grooves in the lower incisors.

The venom has been reported to be lethal to small dogs – and we heard a story of one dog that was bit – he recovered but took ill for over a week before recovering. Published reports of humans being bit indicate swelling and irritation around the wound from the lower incisor but not around wounds from the upper teeth. Solenodon – meaning slotted tooth, pardoxus – contrary to expectations, strange, marvelous.

The snout is attached to the skull by a unique ball-and-socket joint that provides extended flexibility. The solenodon is opportunistic and will eat amphibians, reptiles and small birds if it stumbles upon these. Examination of feces indicates they have consumed snakes and chickens, but these may be from scavenging on carrion. The solenodon will tear apart logs with its strong limbs and substantial claws while searching for prey. The species was not fully described until 1833 by Brant, owing to its secretive behavior

Various names recorded to be used by locals include orso (bear), hormigero (ant-eater), juron (ferret – also applied to the mongoose), and agouta – whose origin is not known.

They are thought to live 11 years or so and have a low reproductive rate with females giving birth to one or two young within the home burrow system. The young will stay close to the mother while accompanying her on nocturnal foraging trips, handing on to her elongated teats by the mouth. Weaning is thought to occur with 75 days and the yearlings may continue to inhabit the same burrow with the next generation of youngsters. This is a rare species and little studied, so much of its natural history is in question. They are a primitive species and thought to have branched off of a common mammal species in the Mesozoic – more than 75 million years ago. And they are not the most graceful of critters, when excited and trying to move faster they are prone to tripping, or it will just decide to sit still, hiding its head. Other than owls they have no predators on the island.

Hispaniolan solenodons inhabit woody and brushy areas and will venture into pastures with patchy trees for foraging – thus they are somewhat flexible in their habitat needs. In 1981 it was declared “functionally extinct” in Haiti due to the extensive deforestation there, but the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust through the Last Survivors research project did locate some in Haiti. The species is doing better in the DR and recent distribution surveys were encouraging, though it is still listed as endangered.

I studied small mammals for my thesis so have always harbored an affection for these scrappy and seldom seen animals. I also have handled the only North American poisonous mammal, the short-tailed shrew of the east coast. AND – who wouldn’t want to go looking for such an intriguing animal? After a year of corresponding with various scientists in Cuba and the DR, and attempting to get onto a research team that was studying the Cuban solenodon as a volunteer and stymied by the bureaucracy there, I made some connections in the DR.

The published descriptions of this rare and interesting mammal are vague and unsatisfactory. For many years it has been commonly considered extinct, and when, in December 1906 I undertook a collecting trip to San Domingo (sic) with the avowed intention of obtaining the solenodon, prominent zoologists stated that the quest was hopeless, one of them saying that I would be as likely to secure specimens of ghosts as of S. paradoxus. –A. H. Verrill, 1907. Notes on the Habits and External Characters of the Solenodon of San Domingo.

Just a few weeks ago Connie and I travelled to Santo Domingo and met up with Jorge Brocca of the SOH Conservacion (an NGO that conducts research and partners with the Ministry of the Environment manage its parks and preserves) and headed west to the border with Haiti and the DR’s Parque Nacional the Sierra de Bahorueo. We based out of the small town of Pedernales and spent the day seeking out indigenous birds and the night rare nocturnal mammals (solenodon and hutia). Jorge and the Last Survivors crew: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/earthvideo/5082935/Rare-footage-of-endangered-Hispaniolan-Solenodon.html

In the evening we met up with a local, Nicholai, who assists Jorge on specific wildlife work because he knows the forests and critters of the area so well. He caught his first solenodon when he was 13. Come twilight we headed off out of town to the park. Once we were in the designated vicinity north of town we parked, got out of the truck, and waited for it to become fully dark. And then we waited for more. Jorge and Nicholai were pleased that it had not rained much yet as it was the tail end of the dry season and this is good for solenodon hunting. We sat on the side of the road and listened in the dark, no one moving. And then listened some more.

I have excellent hearing and could not imagine we could hear anything above the din of a million crickets singing to their hearts content. Supposedly we were listening for the sound of a solenodon foraging among the dry leaves of the forest floor. Twenty minutes, 40 minutes, and an hour went by with me tilting my head one way and then another like some robin listening for worms. Nicholai smoked a cigarette. We listened some more.

Next to me Nicholai suddenly leaned forward intently. I heard it too and pointed in the direction of the sound of what I guessed was 30 yards away — indicated by a distinct leaf shuffling, suggesting an opossum sized animal scurrying around the forest floor. Nicholai quickly motioned – you stay here – and off he went into the forest. Silence again for several minutes and then more leaf shuffling – then Nicholai’s headlamp is lit and he is on the chase and quickly captures a solenodon!! He missed the female as she ducked into her burrow but captured the following youngster – so we took a couple quick photos and then let him follow his mom down the hole. Crazy.

We moved to another nearby stop and within an hour caught an adult female that was pregnant – shown in these photos. With two solenodons in hand we called it an evening and went back to Pedernales and celebrated with a round of Presidente cervesas in the typical outdoor bar/café near the square blasting pop tunes. The next evening we successfully found hutia (another coming OOTW) and were sitting around again talking about these odd and primitive creatures.

Jorge asked – “…so, what do you like better – hutia or solenodon?” I replied without hesitation – “El solenodon!” Jorge took a swig of his beer, smiled broadly and nodded enthusiastically. “Si – a todos les gusta el solenodon!” (Yes! Everyone loves the solenedon!)