SALAMANDER, n. Originally a reptile inhabiting fire; later, an anthropomorphous immortal, but still a pyrophile. Salamanders are now believed to be extinct, the last one of which we have an account having been seen in Carcassonne by the Abbe Belloc, who exorcised it with a bucket of holy water. The Devil’s Dictionary, Ambrose Bierce. 1911.

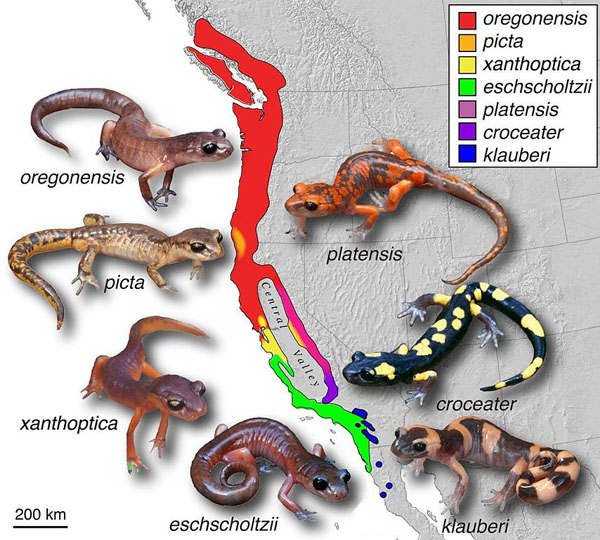

Ensatinas are a group of Plethodontid (lungless) salamanders with a wide distribution from British Columbia, through Washington, Oregon, and California; and down to Baja California. In the Pacific NW they occupy habitats up to 5,000 ft. but in California have been found above 10,000 ft. Their coloration ranges along this west coast gradient from the simple orange/rust color we see here in Washington to the blotched form in southern California. Some have argued that this wide distribution and morphological differences reflects a gradation of speciation – but the debate is ongoing.

These salamanders can be found under logs, brush, or debris by lakes or streams and in other areas with sufficient moisture. Ensatinas, as with all Pelethodon salamanders, must keep their skin moist in order for adequate oxygen exchange. They have no lungs and absorb all their oxygen through their skin and the lining of their mouth. This is known as cutaneous respiration. With all salamanders it is important not handle them excessively as this can dry out their skin and any chemical contamination will be quickly transferred to their sensitive skin.

Ensatina – from the Latin ensatus, sword-shaped, and -ina similar to — a possible reference to the teeth (?). The species name honors the original describer – Johann Friedrich von Eschscholtz (1793-1831) who was a German physician, naturalist, and entomologist. He was among the earliest explorers of the Pacific region and made significant collections of flora and fauna in Alaska, California, and Hawaii. The Genus of the California poppy (Eschschoizia californica) is named in his honor.

They are easily recognizable as they are the only NW salamander with a distinct constriction at the base of the tail. This is the point of the tail that will detach if held by a predator – while the tail continues to wriggle the salamander (hopefully) escapes, though they are not the speediest of critters.

The ensatina is a great example of evolutionary divergence. As the species moved south from its origin in the Pacific Northwest it was not able to inhabit the Central Valley of California and spit its southward movement into the Sierra and into the Coast Range. The subspecies eventually met up the southern end of the valley. All adjoining subspecies within the range are able to breed with one another except the Yellow-blotched (E. e. croweater) and Monterey (E. e. eschscholtzii) ensatinas at the point where they meet at the south end of the Central Valley – which indicates they have genetically separated enough to be unable to breed together. As they moved around the Central Valley they became specialized to their habitats. This “ring-species” distribution is explained well here: Ring Species

They will spend time above ground during the warm and moist spring and autumn, retreating to underground during the winter and summer. Mating takes place from February to April on the ground surface at night. The male will bump the female with his snout during courtship. Eventually the pair will conduct the typical “Plethodon walk” where the male leads and the female follows closely, her front legs straddling the male’s tail. Eventually the male will deposit a spermatophore that is picked up by the female. Eggs are deposited up to 2.5 ft. below ground and the incubation period lasts from 150 to 180 days. The clutch size is 2-25 eggs and are brooded by the female. Courtship

When discovered, ensatinas will remain still, but if further harassed the will stand up tall on their legs, arch their back and tail, and slap or fling the tail, which has a milky secretion. They can make a hissing sound when disturbed. Pinched or bitten tails come loose as a distraction and one study found that 16% of the population had missing tails. Adults are able to regenerate a tail in about 2 years.

Ensatinas ear a variety of invertebrates that include spiders, beetles, millipedes, and crickets. In turn, garter snakes, raccoons, and medium sized birds, such as Stellar’s Jays, will prey upon ensatinas. These small guys don’t wander to far – in a home range study they males only moved about 125 feet in 2 years whereas the females only moved 70 ft. Densities of up to 595 individuals per acre have been recorded.

I’ve seen these salamanders in Oregon and Washington and they seem quite adaptable. While some species have very narrow habitat requirements it seems these guys can be found everywhere. I’ve seen them in areas of great looking habitat and in wetlands with the obligatory shopping carts and old tires – I’ve even found them under tires. So here’s to being a tough little salamander with a diverse group of cousins along the west coast.