Q: Why do birds fly south? A: Because it’s too far to walk. –unknown

It’s autumn and time for many birds to pick up and head south for warmer digs during our winter. One of the champions of migration is the golden plover, which breeds in western Alaska and the Siberian tundra during June – July, typically returning to the same nest spot. In late summer they will make the jump to tiny islands in and around Hawaii, Fiji, the South Pacific, and some make it all the way to New Zealand. That is a one way trip of between 3,000 and 8,000 miles. Across the ocean! With no place to land! And how do you find that relatively small chunk of land in the wide-wide ocean? For a trip from northern Alaska to Hawaii that is 90 hours of non-stop flying.

All this for a rather diminutive bird – it is only about 9-10 inches long with a 17 inch wingspan and weighing a mere 4.3 – 6.8 ounces. It has lived up to 15 years in captivity and has been recorded up to 13 years in the wild. The genus name Pluvialis from pluvia, “rain”. It was believed that golden plovers flocked when rain was imminent. The species name fulva is Latin and refers to a tawny color.

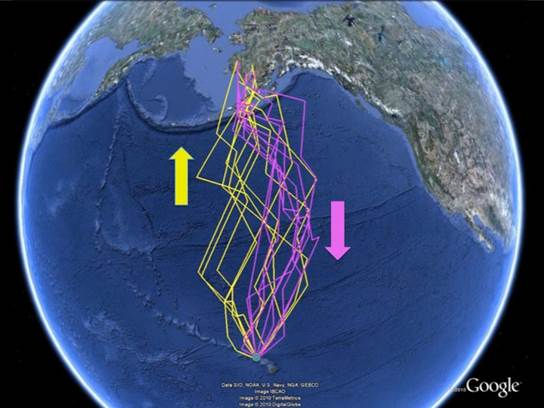

Ok- a side note. You may be wondering how did they get that GPS data on these birds? You don’t want to weigh them down with a large transmitter as they are taking quite the trip. Researches captured plovers in Alaska and then attached tiny data loggers on their legs that collect light levels at regular intervals. These units only weigh 0.7 ounces and represent about 1.2% of the bird’s weight. They transmit no data back so they can keep the size of the unit and battery small. Upon their return to Alaska the birds were recaptured and the data loggers were downloaded and special software converted the light data to a flight track.

And how do you capture a plover? By borrowing technology from law enforcement: Talon Net Other birds have been tracked from Nome – taking eight days to get to Japan, taking a rest and food break before heading south to Sulawesi, an island in Indonesia. Ornithologists hypothesize that plovers use a combination of visual, magnetic, and celestial navigation to find these small specs of land in the ocean.

The birds come back to the same area each year so if they are alive you know where to find an individual on the breeding grounds. For the birds in this particular study they travelled the 3,000 miles in about 36 hours with a maximum speed of 113 miles/hour – with the wind. The return trip took 48 hours. There were some theories that these birds travelled south and then followed the Hawaiian Island chain for navigation – but they took a very direct route. Considering the small target and the need to adjust for wind this is quite the navigational feat. They eat up before they leave but will lose up to 50 percent of their body weight during the trip.

These birds are ground nesters on the open tundra and make use of their tawny color for camouflage while on the nest. They prefer well-drained tundra or side slopes. The nest is a simple one, just a shallow scrape lined with lichen. The typical four eggs are incubated by both parents, who are monogamous. The eggs hatch in 26 days and the young are precocial, ready to run and feed soon after hatching. Similar to other shorebirds, plovers will distract predators by faking a wing injury while luring the predator away from the nest or young. Arctic fox and long-tailed jaegers will take eggs or young. Summer

On the wintering grounds they are much less secretive and can be found lounging around any grassy area including ballfields in and parks. At the University of Hawaii in Honolulu they can be found on the campus grounds and roost at night on the building roofs. I’ve seen them up in the tundra in breeding plumage outside of Nome and in Kauai in a busy park where they seemed quite undistracted by the crowds. Winter

In Hawaiian the bird is known as Kolea, mimicking the call the bird makes. It also means “one who takes and leaves” – aptly describing the feeding frenzy before the long migration. Legend says that as they flew north they may have aided ancient Polynesian seafarers in discovering the Hawaiian Islands. Captain Cook noted them on his journey and wondered if they were flying from some yet undiscovered southern continent. They are the subject of some Hawaiian songs including this one:

‘Olelo No’eau:

Ai keke na hulu o ka umauma

ho’i ke kolea i Kahiki e hanau ai

(When the feathers darken on the breasts,

the kolea returns to Kahiki to breed)

‘Ai no ke kolea a momona ho’i i Kahiki!

(The kolea eats until he is fat, then returns to the land from which he came!)

I ho’okauhua i ke kolea,

no Kahiki ana ke keiki

(When there is a desire for plovers,

the child to be born will travel to Kahiki)

Kolea no ke kolea i knoa inoa iho

(The plover can only cry its own name)

O ka hua o ke kolea aia i Kahiki

(The egg of the kolea is laid in a foreign land)

— from Mary Kawena Pukui, ‘0lelo No’eau: Hawai‘ian Proverbs and Poetical Sayings, Bishop Museum Press 1983