The woodcock is a small shorebird of the eastern North America. Though it is in the Family Scolopacidae with other shorebirds and sandpipers it is a bird of young forests. Its camouflage plumage allows it to spend most of its time on the forest floor. It prefers young forests that contain a fair amount of brush and open space, and because development and the maturing of eastern forests following historic logging the population of woodcock in North America has been declining about 1% per year since the 1960s.

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan calls for the reestablishment of populations to levels seen in the 1970s through habitat management and preservation. The woodcock is classified as a gamebird by state fish and wildlife agencies and is hunted – though you probably need about five of these guys for a decent sandwich. I can’t imagine they are easy to shoot as you’ll be walking through the woods and they will just sit still until you just about walk on them when they will explode off the forest floor in a bust of wing beats and take off among the trees in a zigzagging flight – giving you quite the start.

Woodcocks are a plump little bird, 10-12 inches long and weigh only 5 – 8 ounces. They have a long bill that is up to 2.75 inches long. For a small bird they have large eyes that are set far back in the head and they have quite the field of vision. In the horizontal plane they can see 360 degrees – so they don’t miss a trick here, and they can see 180 degrees in the vertical plane – which is probably the largest field of vision for birds. So why do they need such a wide field of vision? Maybe it’s because they spend so much time on the ground and need to keep a steady watch for potential predators on the ground and in the air.

The woodcock’s bill is described as “prehensile” a term used to describe an appendage that can grasp – such as the tails of New World monkeys that can hang from their tails. The bill of the woodcock has a unique bone/muscle arrangement that allows the bird to open and close the end of the beak while it probes in the soil for invertebrates and especially earthworms. The tongue is rough and aids in grasping prey. Woodcocks just love, love, love to eat earthworms, their primary food. They prefer moist soils among thickets, which provide some cover and protection. They also will eat insect larvae, snails, spiders, millipedes, ants, and other invertebrates.

These birds are crepuscular – meaning that they are most active at dawn and dusk – as opposed to diurnal (daytime) or nocturnal (night). Woodcock migrate south to avoid the snows of northern winter. They migrate at night flying at low altitude in small flocks that have been clocked cruising along as fast as 28 miles an hour – which is not so fast, but not bad considering the aerodynamics of this bird are probably comparable to that of a VW bus. They will migrate in October when the ground starts preventing them from feeding, heading south for warmer weather and better foraging.

The other name I know this bird as is a “timberdoodle” – seriously! Supposedly it’s also referred to as the bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse – none of which I’ve heard of before. The bird has an interesting mating routine – in the spring males will sit on the ground within their claimed “singing grounds” and call. They prefer moonlit times at dusk and dawn to perform their flight displays. The male’s call is described as a nasal peent . Here’s an example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Owj52XhoxI

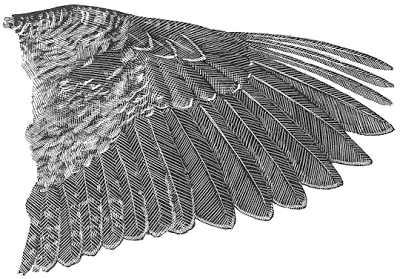

Also note in that video the flexible end of the bill. After calling for a while the male will fly up in a spiral up to 300 ft, calling while rising. Towards the top of the flight his outer primary (main wing) feathers producing a buzzing sound as the air rushes over them. The three outer primaries are modified and are much narrower than the others – facilitating this noise making – which apparently is attractive to a prospective mate.

The male then descends quickly in a zig-zaggy manner landing, hopefully, next to a female that has been attracted by his display.

I went to undergraduate and graduate school back east. In undergraduate my B.S. in Natural Resources Management included work in fisheries, forestry, and wildlife. One time during some forestry assignment I was walking through a large woodlot with the landowner – an old timer who had managed this oak-hickory forest on his property for 50 years, conducting selective harvest every other year.

His well worn hands with knuckles big as hickory nuts depicted a life around a working forest. It was dusk in early spring and we were walking back towards his barn and pasture when we heard a woodcock. I opened my mouth to say “woodcock!” but he spoke first and said “timberdoodle”. I had never heard this name and stopped and mouthed whaaaaat? He realized this youngster still had a lot to learned, stopped and gave me a wry smile from beneath his hat, nodded a few times and repeated – “timberdoodle”. How could you not love that name?