There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved. – Charles Darwin, Origin of Species.

he fisher is a carnivorous mammal within the weasel (mustelid) family that is native to North America. To make things confusing, of course, the fisher doesn’t eat fish. Rather the name comes from the word “fitch” in reference to the European pole cat, whose pelt has a similar look. In French the pelt of a polecat is referred to as a fiche or fichet.

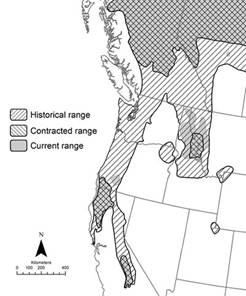

The range of the fisher has been drastically reduced due to forest fragmentation and trapping for its fur. It was not until the 1930’s when protections were put in place for the fisher. Historically the fisher occurred south into the Appalachians of Tennessee and North Carolina. The present range includes forested regions of Canada, New England, northern New York, northern Minnesota, northern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Fishers prefer forests with a high percentage of canopy closure, abundant woody debris, large snags and cavity trees and understory vegetation. Riparian areas are used extensively, especially for travel corridors. Interestingly, 48 of 55 records of fishers in Washington were from below 3,000 ft. elevation – and none were above 6,000 ft. suggesting an avoidance of heavy snowpack.

Fishers are opportunistic feeders – mostly preying upon snowshoe hares and porcupines, but also consuming insects, berries, nuts, and fungi. Stomach content analysis also indicates they will eat birds, small mammals, and deer carrion and they have been observed feeding on deer carcasses. They are one of the few animals that will prey on porcupines – repeatedly biting them in the face until they succumb.

In SW Oregon prey items at a den included Steller’s jay, northern flicker, pileated woodpecker, ruffed grouse, deer fawn, snowshoe hare, California ground squirrel, northern flying squirrel, Douglas squirrel, and porcupine (!!!).

Females will become mature in one year and a reproductive cycle will take just about one year. Males can produce sperm within a year but are note effective breeders until year two. While mating takes place in March through April, the fertilized blastocyst delays implantation into the uterus for 10 months until mid-February of the following year when pregnancy begins.

Gestation takes about 50 days and the female will give birth to one to four kits. Thus, delayed implantation (also referred to as facultative diapause) allows fishers and other mustelids to give birth when seasonal conditions are most favorable for the survival of the kits.

The kits are born altricial – blind and helpless, and will take up to 3 weeks to learn to crawl around. After 7 weeks they will open their eyes and a week later will start climbing around on trees. Fishers are mainly terrestrial by will climb trees to reach den sites or prey items. The young are dependent on mom’s milk for 8 – 10 weeks. They will get nudged out of the den at 5 months and after a year will have established their own territory. Life expectancy is about 10 years.

Fishers are solitary animals and mark their territory with feces and urine and using glandular secretions on logs, stumps, and snow piles. Plantar glands on their hind feet become larger in the breeding season and may deposit scent while walking.

They are known to be secretive animals and appear to avoid humans. But occasionally they will take up residence beneath a structure or near occupied dwellings. There have been examples of fishers raiding suet feeders put out for birds. Home ranges average 15 – 19 mi2 for males and 6-8 mi2 for females. They will generally travel abut 3 miles a day in the winter and more in the summer.

The Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have reintroduced fishers to the Olympic National Park and in 2009 documented the first breeding pair in over 50 years. Just this week fishers were released in the North Cascades National Park near our project site at the Skagit Hydroelectric Project – Fisher Release

bout 20 years ago I was driving back from a climbing trip on the east side of the Cascades with my buddy – he was driving as we recently came over the west side of Snoqualmie Pass while I was semi-dozing after the long day. A dark streak passed on the road shoulder as I startled to alertness and quickly swiveled my head around.

“What was that?” asked Dick – “I’m not sure, but I think that was a dead fisher by the side of the road”. “And…?” – “Well” I said, “they are extremely rare – if that was a fisher, and it certainly looked big enough – that would be pretty cool. We could pick it up and bring it back to the University of Washington – Keith Aubry, their mammal guy, would be stoked”.

So we decided to double-back, which was no small feat given the lack of exits. We had to continue another 10 miles west, then travel back east for 20 miles or so, and then another 5 miles or so back west to find the critter. Heading west again we kept our eyes peeled – and eventually we could see the dark outline of the animal on the shoulder in the distance. Dick parked the truck just beyond it and we both got out and walked up to it.

Standing above our quarry I was more precisely able to identify it – a 1990-era bumper off a Toyota pickup. I looked at Dick and he said “You are so buying a couple rounds when we get back to town”. Needless to say we didn’t return our prize to UW.