From Arroyo de Elmedio to Arroyo de Pabon, fifteen miles. From Arroyo de Pabon to Mananciales, ten miles. As we pursued our journey late in the evening, we saw large flocks of ostriches (Rhea), which had come forth from the long grass to refresh themselves with water. On the following day some of our attendants rode a considerable way into the grass, and brought back about fifty eggs of these birds. The heat of the sun being very great, and each of us having put some of them. Charles Darwin, Voyage of the Beagle, 1807.

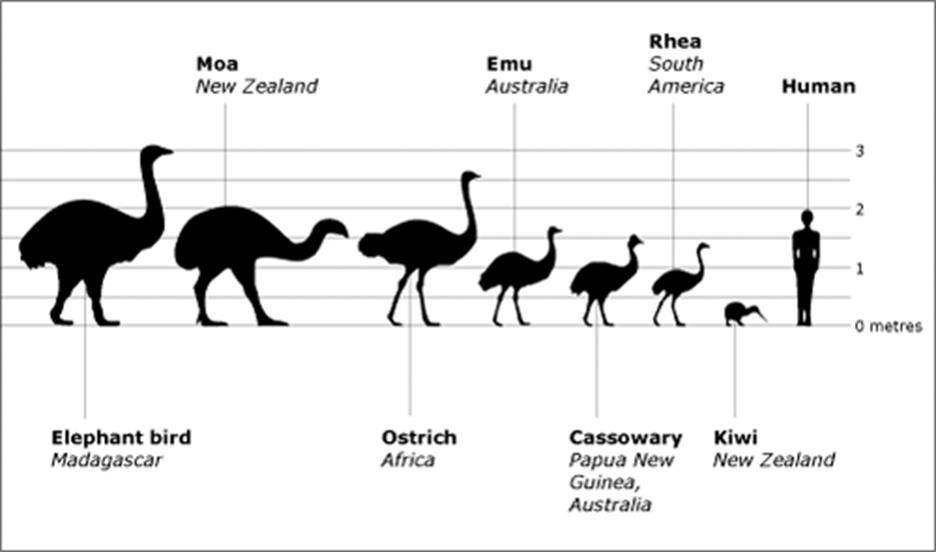

Rheas are found in South American and are large birds of the group referred to as ratites – flightless birds with long legs and without a keel on their sternum. This includes rheas, ostriches, emus, cassowaries and the smaller related kiwi. Most birds have a keel on their sternum where the strong flight muscles attach, which ratites lack.

Ratites share a common ancestor going back to when the earth had just one combined land mass – Gondwana. Recent DNA analysis indicates a complicated divergent branching pattern of evolution as these birds developed and refined similar traits.

The loss of flight allowed birds to eliminate the energy costs of maintaining large, flight-enabling muscles. The basal metabolic rate of flying birds is much higher than that of flightless birds. Current research indicates that these birds evolved during a time without predators – during the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event, when ¾ of the plant and animal species disappeared. The event was caused by a large asteroid crashing into the earth, which devastated the global environment, causing “impact winter, halting plant photosynthesis. The ratites subsequently evolved their large size.

In Greek mythology Rhea was one of the Titans, daughter of Uranus and Gaea, sister and wife of Cronus. Her name means “that which flows” or “earth-rooted”, a reference to the bird’s inability to fly.

Two species of rhea occur in South America – the American rhea (greater rhea) (Rhea americana) and Darwin’s rhea (lesser rhea) (Rhea pennata) (pennata = winged). Locally rhea is known as nandu guazu. Nandu is the common name in many European languages – In Guarani the name translates to “big spider” – possibly referring to the habit of opening and lowering alternate wings as they run. They can peg the meter at 40 mph. Fast Bird

Greater rheas inhabit grassland and savannas of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. They weigh 45 – 60 lbs. and are the largest bird of South America. Adults are almost 5 ft tall. Darwin’s rhea stands about 38 inches tall and weigh 33 – 63 lbs. The sharp toes on rheas are a formidable weapon.

Darwin’s rhea is mostly an herbivore, occasionally eating the odd small animal. Greater rheas also mostly forage on vegetation, particularly seed and fruit when in season. They also prey upon insects, scorpions, small rodents, reptiles, and small birds. Like many herbivorous birds they eat small pebbles that are stored in their gizzard and facilitate grinding of plant material.

Following winter, the birds form three group types – single males, flocks of 2-15 females, and large flocks of yearlings. As winter approaches the males become increasingly aggressive towards one another. Males are polygynous, females are serially polyandrous. This means that females move around during the breeding season, mating with a male a laying their eggs before leaving the male to incubate, moving on to another male. Males attend the nests, taking responsibility for incubation and the hatchlings. In some cases, males will use less dominant males to help incubate and protect eggs – sometimes breeding with other females and amassing a nest of up to 80 eggs.

Cougars and jaguars are the only predators of adult rheas, while caracaras, armadillos, and grisons may prey upon the eggs or young. Rheas are used for feather dusters and skins are used for cloaks or leather and the meat is a stable in some areas. The gaucho people hunt them on horseback using boleadoras, three balls joined by a rope thrown to tangle the bird’s feet.

The bird is farm-raised in the U.S. and other countries.

In the early 90s I was in Patagonia for an extended trip and we needed to get from Puerto Natales, Chile to Carafate, Argentina, one leg of travel to get to El Chaltan. There was a weekly van service – two 12 passenger vans, for the 8 hr. trip – all on dirt roads across broad, dry savanna. I was dozing with my head on the window and occasional jolted awake when we fish-tailed through alarmingly large, muddy waterholes. As we zipped along trailing a large dust plume I would get glimpses of rhea running away from the road in small groups. No houses, farms, or people were in sight.

After 4 hours we stopped at a wayward rest area with a worn Argentinian flag snapping in the ever-present wind. We had some Nescafe and a stale pastry. My climbing partner and I wandered to the back of the building to view the landscape and delay getting back in the van. As we came around the corner we surprised a group of 10 rhea. It was if the music suddenly stopped – they pivoted around to stare at us in unison. My first though was I hoped these feathered dinosaurs weren’t coming for us. We stopped. The steady wind kicked up grit in bursts, the endless ocean of dry grass swayed, and these ancient birds, slowly and cautiously, went back to feeding.