In a frigid land that we humans often fear to tread,

Lies an ecosystem that almost anyone would dread.

Throughout this region, where gale force winds blow,

Lives a tiny creature hidden against the blinding snow.

—Glen Bergen, The Arctic Fox

As is implied by its common name, this is a fox of the northern climes with a circumpolar distribution near or above the Arctic Circle. It inhabits tundra, pack ice, some boreal forests and is found at elevations up to 9,800 ft. and has been observed on sea ice close to the North Pole. It is the only native land mammal that inhabits Iceland and settled here during the last ice age crossing over the frozen sea.

This is a pretty small fox with a length of only 18 – 27 inches and a tail of another 12 inches. Males average about 7.5 lbs. but can weigh up to 20 lbs.; females are generally smaller weighing up to 7.2 lbs. In most of its range it displays seasonal coat colors – white in winter and brownish to gray-blue during the summer to blend in with its surroundings. The two color phases are referred to as white and blue.

Basically they will eat anything they can catch including lemmings, voles and other rodents, hares, birds, eggs, fish, carrion and mollusks. They will scavenge on kills left behind by larger predators such as polar bears, and in scarce times will eat their feces. Foxes also are known to prey on ringed seal pups and to forage on berries and seaweed. In Iceland they prey mostly on birds and bird eggs during the summer while maneuvering along cliff faces. When food is overabundant foxes will bury (cache) extra for use later. Coastal Icelandic foxes do not change white during the winter because their foraging opportunities are concentrated along the shoreline while interior Icelandic foxes change white during the winter. They will listen for prey rustling under the snow and jump up and plunge nose-first to find the rodent – great video of this technique here: Jump and Plunge

Arctic foxes live in dens that are frost free and typically within slightly raised ground such as eskers (glacial melt-formed sediment mounds). Their tunnels can be quite extensive and cover up to 1,200 yds2. They are monogamous and mate for life, maintain a breeding territory around the den. Foxes mate in April/May and have a gestation period of about 52 days. The litters average 5-8 but up to 25 kits have been recorded for one litter (largest litter size in the Order Carnivora). Both parents raise the young, which are weaned in 9 weeks.

Considering its size and where it lives, it is quite the wonder that the Arctic fox does not hibernate but stays active all year. Only the sea otter has a denser fur. During the autumn and in anticipation of a leaner winter the foxes will increase their body weight up to 50%, building important fat reserves.

Foxes are especially adapted to their freezing environment and they don’t have the need to shiver until temperatures drop to minus 94° F. They have a multi-layered pelt for prime insulation, and a countercurrent heat exchange in their legs – where arteries carrying warm blood flow close to veins returning cooler blood to the heart – that allows their paws to retain core temperature. In addition they carry high amount of body fat. The Arctic fox has a compact body shape, short muzzle and legs, and short, thick ears – all of which contribute to a low surface to volume ratio that reduces body heat loss. This follows the ecological principal known as “Allen’s Rule”, which notes that more northern mammals have shorter limbs and more compact bodies to reduce heat loss, and is named after Joel Asaph Allen, a zoologist who among other accomplishments, was the first curator of birds and mammals a the American Museum of Natural History.

I’ve seen these foxes in Alaska several times – once above the Arctic Circle near beautiful Kotzebue, and a couple times in Denali National Park and State Park. Once was in late autumn so this animal well on its way to having a full white coat.

I was in Iceland earlier this summer and spotted a couple on the remote peninsula of the Hornstrandir Nature Reserve, which supports the greatest densities of Arctic foxes in the country.

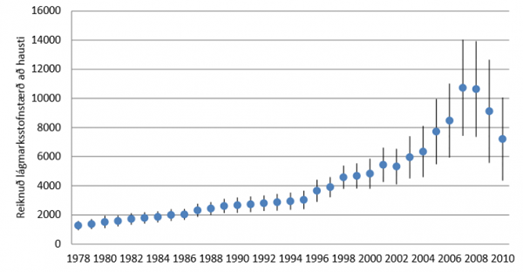

Arctic fox numbers have in Iceland have increased substantially since the late 1970’s when their population was below an estimated 2,000 individuals and has climbed to over 10,000 recently but has dropped a bit the past few years. While not totally clear, a majority of scientists point to a significant increase in the success of seabirds that nest on ocean-side cliffs (a major fox prey item), which in turn is a result of rising ocean temperatures and a greater prey base.

Foxes can be hunted at certain times of the year in Iceland, except on in the Hornstrandir Nature Reserve where they are protected. Ranchers do so to protect sheep, as foxes will attack lambs and sometimes adults. In addition, eider farmers – folks who collect eider down from wild eider nests – also hunt foxes to protect their harvesting grounds.

We did see two foxes along the cliffs in Hornstrandir but they quickly ran over the rocks and out of sight – so I had to settle with a few photos taken at the Arctic Fox Center in Sudavik. The real research is conducted in Hornstrandir Nature Reserve, but the center has a wealth of information on the natural history of foxes. You can take an interesting vacation and volunteer as a field researcher – pack some warm and waterproof clothes http://www.melrakki.is/volunteer/arctic_fox_monitoring_volunteers/

And – they have two orphaned foxes in a pen in the back of the building. Apparently Iceland law was changed recently and orphaned foxes cannot be released to the wild so these are the last two the center will support and they will live out their life here. From now on any orphaned foxes will be euthanized.