It’s better to be a young June bug than an old bird of paradise. Mark Twain

This is a large genus of New World scarab beetles – so taxonomically they are not bugs – which are within the Insect Order Hemiptera, or true bugs. The Phyllophaga are commonly known as May beetles, June bugs, or June beetles. They are very common and range in size from 0.5 to 1.4 inches in length, are black or reddish brown and have no distinct markings. Phyllophaga – from the Greek phyllon (leaf) and phagos (eater).

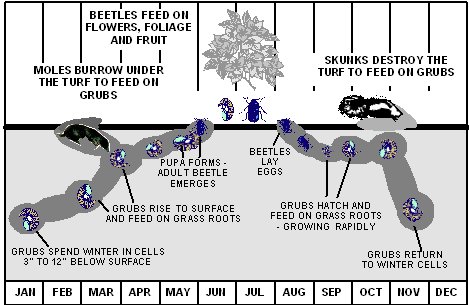

So as indicated from the Genus name, the adults feed on the leaves of trees and shrubs – a feeding strategy than classifies them as chafers. Females lay 60-75 eggs in mid-summer that hatch into white grubs. In contrast to the adults, the young larvae (grubs) live underground and feed on the roots of grasses and other plants. These larvae will pupate underground in the autumn and then emerge to the surface as adults in the spring. If the larvae are particularly dense underground, they may attract the attention of avian predators – crows are known to pull back lawn while scrounging for them, like lifting the carpet to find tasty morsels. Similarly mammalian predators such as skunks, moles, and armadillos will rummage through turf to find these grubs. Thus, these grubs are considered pests in turf farms and golf courses.

The most common June bug is Phyllophaga crinita but these insects, especially the larvae, are particularly difficult to identify to the species level. As noted in one publication by 4 Ph.D. entomologists “The keys are out dated, and identification is based on physical characteristics of the grubs that can be recognized only by individuals with special training and experience”. That’s one niche field of scientific inquiry.

June bugs are common across North America from Nova Scotia to Mexico. The adults are more evident than the larvae – as the adults are attracted to lights and continually bonk into door and window screens. Kids sometimes entertain themselves by tying a length of thread to a June bug and letting it fly around on this leash.

I worked back east as a fisheries biologist with a couple friends from graduate school. March through October was field work and the colder months were limited to crunching field data or staring through dissecting scopes to identify invertebrates from fish stomach samples or aging fish scale/spine samples.

One of my buddies, Tim, grew up outside of Pittsburg and one rainy summer evening he was standing under the eaves of a garage talking with a high school girlfriend when one of the June bugs flying around the outdoor light made an erratic loop and threaded the improbable needle into his left ear. Tim yelled and jumped around trying to dislodge the invader. They went inside and his girlfriend’s family put a flashlight near his ear hoping to draw it out, then poured olive oil into his ear as the June bug would not come out. The pain subsided after 15 minutes or so, and everyone scoured the floor looking for the little critter but couldn’t find it.

Flash forward 10 years. Tim is at one bench identifying copepods and I’m next to him counting ring annuli on small mouth bass scales. Tim is scratching his ear, and then picks up a pair of small forceps, uses that to scratch the inside of his ear, then pulls out a June bug leg!! As a curious scientist he investigates further and extracts a whole June bug encased in wax from his ear! Whaaaat!! That’s when I first hear the June bug story. Tim is a big, bear of a guy with a red beard and a perennially optimistic attitude. “Well”, he says, “ya know, I always could hear better out of my right ear compared to my left”.

I always thought it some great circle of fate that a beetle, similar to the scarab beetle that was prominent in Egyptian religion, was mummified for a decade with Tim.