A loaf of bread,’ the Walrus said,

‘Is what we chiefly need:

Pepper and vinegar besides

Are very good indeed —

Now if you’re ready, Oysters dear,

We can begin to feed.’

Lewis Carroll, The Walrus and the Carpenter.

This is a very large flippered marine mammal found in the arctic and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. How large? Well – big guys will tip the scales at 4,500 pounds but most weigh between 1,800 and 3,700 pounds. A 16 ft. long walrus was shot in 1910 and its hide alone weighed 1,000 lbs. – since the hide is about 20% of the total body weight this animal weighed an estimated 5,000 lbs. For comparison, a Honda Civic weights about 3,000 lbs. Of the pinniped species (seals) only two elephant seal species are larger.

There are two subspecies of the walrus – the Pacific and Atlantic subspecies. Some scientists recognize a third subspecies that inhabits the Laptev Sea of the Arctic Ocean, though there is not universal agreement here. Adult walrus are distinguished by their protruding tusks, their stiff whiskers, and large body size. They live in relatively shallow waters along the continental shelves and spend most of their time on sea ice, diving to forage for mollusks along the seabed.

Prior to annihilation by humans, their range used to extend south to New York City and southwest to Great Britain. Walrus generally move north each year following the retreating ice edge and then south as the ice advances in October. Pacific walruses also move north in the spring on floating ice. Their ivory tusks were in demand but today hunting is limited to Inuit and other native peoples.

They have a thick hide and neck with a pair of air sacs in the neck that can be inflated that help buoy them while sleeping in the water. Their thick hide can prevent them from being dragged off by a polar bear. Polar bear vs walrus Generally, bears can only manage to kill smaller, subadults or pups.

Walrus have a dense layer of blubber that allows them to be quite comfortable in near freezing water. Underwater their skin appears white, but on land and the greater surface blood circulation they can take on a pinkish hue. They have scant brownish hair on their body and blubber can account for one third of their body weight.

Walrus have a powerful sucking action thanks to a vaulted mouth working in concert with a strong tongue. This allows them to extract worms and other invertebrates from the mud and to suck clams and snails from their shells. Because of their foraging strategy and rooting along the sea floor, they are referred to as the earthworms of the subpolar seas. They will feed in shallow water until the ice begins to form and then will keep breathing holes open as long as they can, and then retreat to offshore leads (open water channels) as the pack ice closes up. In the summer they haul out on all kinds of shoreline including cobble beaches, rock, and boulder beaches.

Tusks can grow up to 3 ft. long and are primarily used for defense and establishing dominance. Scientists once thought that walrus used their tusks to rake the seafloor for mollusks, but analysis of scrape patterns on the tusks indicates that they are just dragged along while walruses root around with their muzzle. They may use there tusks to propel themselves along the sea floor or to help them climb up onto pack ice.

Walrus are in the order Carnivora and are the only living member of the family Odobenidae –which is one of the three lineages of the suborder Pinnipedia with the true seals (Phocidae) and eared seals (Otariidae). Odobenus comes from odous (Greek for ‘tooth’) and baino (Greek for ‘walk’), likely because they use their tusks to pull themselves out of the water; and the species name rosmarus is Scandinavian – the Norwegian manuscript Konungsskuggsja (1240) refers to the walrus as rosmhvalr.

Walruses are very gregarious – feeding, hauling out, and migrating in densely packed groups. In cool weather they lie around together in tight packs with dominant males taking the best position and subordinate ones shuffled to the periphery of the herd.

Walruses live to 20 – 30 years in the wild and males reach sexual maturity in about seven years but typically do not mate until about 15 years old. Breeding occurs January – March and gestation lasts 15-16 months.

The fertilized blastula (early embryo) suspends development and just hangs out for a few months before implanting in the uterus. This strategy of delayed implantation, which is common among pinnipeds, evolved to optimize the mating and birthing time to ensure the highest survival of the young. If the blastula implanted immediately, and the young were born three months earlier, then conditions would be too harsh for the young. So instead of being born in February the young are born in May – quite a difference in the polar regions. A number of land mammals also employ this strategy.

I’ve only seen this species once out in the wild – from a long distance away they just appeared as little dots in the water. I was up on the spit of land called Port Clarence, just below the Bearing Strait on Alaska’s Seward Peninsula (look it up on Google Earth). I was visiting the Coast Guard station there and the LORAN tower (1,350 ft. tall) that was planned to be decommissioned as GPS became more reliable. When out and about on the spit you had to have a Coasty and his .30-06 rifle with you because of the possibility of encountering either or both grizzly bears or polar bears. Yikes! The tower and buildings have since been removed but the airfield remains.

We didn’t see any bears while out on our surveys, but did see the walruses in the distance. There is a small Inuit village across the bay and they regularly hunt for beluga and walrus and then drag their prize onto the Port Clarence spit and clean the carcass, leaving the bones for the scavengers. Between these skeletons, and the remains of whales that are beached from the Bearing Sea, the beach was littered with whale and walrus bones.

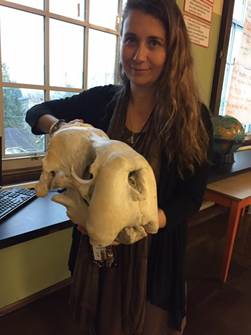

I came across a nice looking walrus skull (minus tusks of course) that had the upper and lower jaw, and only some minor skin attached. I was admiring it and said I like to take it back to add to my skull collection and the Coasty I was with said sure, toss it in the back of the pickup. We drove it back to the storage shed and he pulled out the pressure washer and I went to work. Then we put it in a weak bleach solution overnight. The next morning I got up early and drained it and rinsed it, put it in a plastic bag and it barely fit in a 5 gallon bucket with a snap lid.

I tossed it on the small plane back to Nome and the following day toted it into the small Alaska Airlines terminal there. While checking in the bucket, the Alaska representative said – “….do you have any liquid or bloody things in there?” – so I started going into the explanation – wildlife biologist – big skull – dried – while punctuating the story with my gesticulating hands – but she cut me off and said, “ok, that’s fine” and off it went to checked baggage. It is Alaska after all.

Back in Seattle Connie picked up my colleague and me from the airport. She eyed my orange plastic bucket with suspicion asking – “What’s in that!!??” I said “it was a long story – I’ll show you when we get home”. She’s a middle school science teacher and has had the skull among others in her classroom for over a decade. It’s one of the kids’ favorites.

If you are interested in seeing the skull, I borrowed it from the classroom for the day and it’s sitting on the table in the common space near my office.