They sat there, on the tower, these Trojan elders,

like cicadas perched up on a forest branch, chirping

their soft, delicate sounds. –The Iliad, Homer.

Cicadas belong to the Order Hemiptera, the true bugs, and most are in the family Cicadidae, with two species in the Tettigarcidae. Hemiptera are different from other insects in that both the nymph and the adult forms have a beak (rostrum) that is used to suck plant fluids (xylem). They both eat and drink this way.

Females deposit a rice-sized egg in a groove in a tree limb that she makes with her ovipositor. This groove provides shelter and also exposes tree fluids, which the young cicadas feed upon. Once hatched, the cicada begins to feed and at this point resembles a termite or a small white ant. It eventually crawls from the groove and falls to the ground where it will dig in and feed on the tree roots. The young cicada will stay underground from 2 to 17 years depending on the species, where it will tunnel around and continue feeding.

After 2 to 17 years the cicadas will emerge from the ground as nymphs and climb the nearest tree. They will then shed their nymph exoskeleton allowing their wings to inflate with fluid and their adult skin to harden. Once these items are set they begin their brief life as an adult cicada or imagoe, where they spend their time in trees looking for a mate, continuing the life cycle loop.

Nymph emerging from exoskeleton: Transformation

In North America there are over 190 varieties (species and subspecies) of cicadas and over 3,390 worldwide. They occur on every continent except Antarctica. They display three life-cycle types:

· Annual – emerge every year,

· Periodical – emerge all together after long periods, such as Magicicada septendecim, which emerge every 17 years, and

· Proto-periodical – those that may emerge every year but every so often they emerge in heavy numbers.

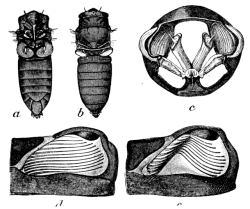

Cicadas are best known for their songs. The male adults sing by flexing their tymbals, which are drum-like organs found in their abdomens. Small muscles rapidly bull the tymbals in and out of shape – thinking of bending a Snapple bottle top in and out. The cicada sound is intensified by its mostly hollow abdomen.

Periodical Cicada. c- muscle and tendon

connections, d & e – bending of tymbal

The loudest North American cicada is Neotibicen pronotalis, which is found along the east coast and in the mid-west and can achieve a stunning 108.9 decibels.

Put the volume on maximum for this short video and it provides a hint of what they sound like: Cicada Chirping

If you have not experienced a brood emergence it is a pretty cool thing. Growing up back east I was able to see and hear a handful of these. For 4 years I worked in Washington D.C. but for 2.5 of those years I lived with a buddy in an old farm house on 40 acres just across the upper Potomac River from Harpers Ferry. The Appalachian Trail was on the ridge above us and we were surrounded by oak-hickory forests. One summer there was a 17 year brood emergence.

The noise was nothing short of incredible. You would walk outside into the humid summer day and the sound would just envelope you. It was if a million small alien invaders were chirping away, and when it got to a point where you thought it just couldn’t get any louder – it did. The air was occasionally punctuated by flying cicadas – portly things not known for their aerial agility – which would more often than not bonk you in the head on their way to a tree. Their nymph exoskeletons were all over the trees and often piled up on the ground.

And of course there is a subculture of hobbyists devoted to cicada watching, so you can go to their website and find out when and where is the next big emergence. New York State is looking good for a summer vacation in 2018! Emergence Schedule