Ambystoma maculatum–

Big mouth–hidden

under the final log

with a worm and centipede for a meal.

I exclaimed Rare species!

but it’s common, fossorial

lives in moist woods

under cemetery stones and memorials.

—-From Exponential Decay Function, Robert Ronnow

These are large salamanders (up to 8 inches long) of the family Ambystoma – the mole salamanders. Mole salamanders are endemic to North America and get their name from living the vast majority of their lives underground, surfacing only occasionally to feed at night and in the spring to breed in shallow vernal pools (temporary) in the forest. Mole salamanders are easily identified as a group by the wide snout and protruding eyes, thick appendages, and prominent coastal groves on the side of their body. They are a rather robust looking salamander. Spotted salamanders are common within in their range that extends from Nova Scotia to Lake Superior and south to Texas and Georgia. It is the state amphibian of Ohio and South Carolina.

Ambystoma – Greek, amby – cup, and stoma – mouth. Maculatum is Latin for spotted. Spotted salamanders are quite striking with a dark brown to black background on top and a lighter underbelly. They have bright yellow spots on top that number from 24 to 45, arranged in two irregular rows from head to tail. Unspotted individuals have been recorded but are extremely rare.

Spotted salamanders will make use of burrows dug by small mammals. One study determined that the burrow of the short-tailed shrew was the most commonly used and deeper burrows by white-footed and deer mice also were used. And telemetry studies show that spotted salamanders will travel over 500 feet from their underground burrows to temporary breeding ponds. Interestingly they will enter and depart these temporary breeding ponds in the same spot year after year and use a travel corridor that doesn’t vary much – thus, are pretty efficient in getting from point A to point B.

When temperatures rise to above 50 degrees F and humidity is high these salamanders will make their way to the breeding ponds. A warm spring rain will often initiate a march to breeding ponds by hundreds of salamanders. Males and females will rub against one another and the males produce a small blob of sperm – a spermatophore that the females pick up with their cloaca. Each female will take up spermatophores of several males and males fertilize several females.

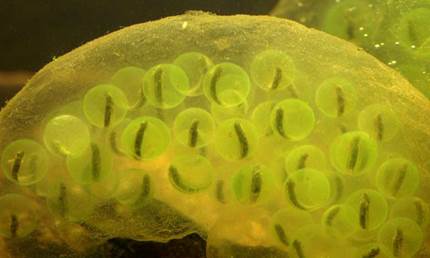

Females will lay about 100 eggs in a mass that is attached to aquatic plants. The outer jelly layer of the egg mass varies between two types – on with a clear appearance that contains a water soluble protein and the other that is white and contains a crystalline hydrophobic protein. Some researchers think these variations take advantage of the wide range of nutrient levels in different ponds while also acting a deterrent to predation from wood frog larvae.

The egg mass also has a symbiotic relationship with green algae. The jelly mass prevents the eggs from drying out but also inhibits the exchange of oxygen from the surrounding water. The algae, through photosynthesis, produces oxygen that is metabolized by the embryos. In turn, the embryos produce carbon dioxide that is used by the algae.

Very recently researchers found that algae actually inhabits skin cells of the salamander. This is pretty significant as it is the only known relationship of an algae within a vertebrate species. It is a common phenomenon with some invertebrates, such as sponges. Right now it’s not clear how this relationship works, but the salamander has a suppressed immune response otherwise the algae would be attacked by the body’s defenses.

The eggs will hatch within a month or two, dependent upon the water temperature. The larvae have gills and are fully aquatic – but metamorphose into terrestrial forms as the vernal pools evaporate. They will then join their counterparts underground. Laval survive on zooplankton (microscopic animals) and as they grow larger will start to consume isopods and amphipods. The hatchlings are protected from fish predation because the vernal breeding ponds are temporary, but they are preyed upon by tadpoles, frogs, crayfish and some caddisfly and midges. Adults are eaten by skunks, raccoons, garter snakes, and other salamanders.

Spotted salamanders take 2-3 years to become sexually mature, live up to 20 years in the wild, and captives have been known to live to 30 years. Adults feed on a variety of invertebrates including crickets, insects, worms, spiders, slugs, and centipedes. Adults have poison glands in their skin, concentrated on their backs and tails, which release a sticky white, toxic, fluid when it feels threatened. The bright yellow spots are thought to act as a warning of this defense.

I came across these creatures when I was young, attending a Boy Scout camp in a state forest in northern New Jersey. My ritual was to get up early and spend about an hour before breakfast turning over rocks on the steep talus slope behind our tent platforms. I distinctly remember rolling wedging out a basketball-sized rock and there sat a large, adult spotted salamander. I had never seen a mole salamander and they were quite huge and fat compared to the small red-backed salamanders I commonly found. I was just stunned and looked agape at this wondrous critter. It looked up and then scampered for a space between the underlying rocks and was gone. There was enough time to get my mitts on him, but I missed my chance. It certainly added to my fascination about herpetology.

Much later in life when I was working on the Susquehanna River as a fish biologist I rented a big farm house with four other. We finished a group dinner one evening when Brian, always the naturalist, said – “hey, I saw some spotted salamanders breeding in some rock pools near the river the other day – I bet tonight is a good night to see them”. It was 11 pm and we were 20 miles from town, so there wasn’t much else to do. We piled in to the car and drove to the river, hiked in the full moon about a hundred yards, as Brian led us to a series of rock terraces along the river. There, in a half dozen or so pools were about 100 spotted salamanders doing their thing. We just sat on the various tiers of ledges watching these beautiful little animals in the moonlight – absolutely fascinated by them.