From 50 to 100 Gyrfalcons were delivered to Moscow annually, the highest numbers delivered during the reign of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov (1645–1676). Gyrfalcon trappers in the Russian Arctic in the 13th -18th Centuries, Jevgeni Shergalin.

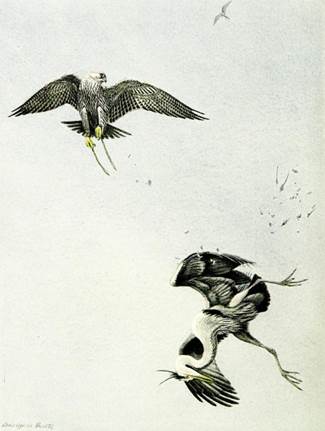

This is a bird of the northern tundra and the world’s largest falcon, weighing up to 4.5 lbs. and 22 inches long. They have a wingspan of about 32 inches and are extremely powerful flyers. I’ve heard them referred to as the Arnold Schwarzenegger of falcons. While other falcons will hunt birds from above, gyrfalcons also have been observed to fly from a perch directly up to a prey item and they are often such an intimidating presence that a duck may just give up, accept its fate, and land on the ground. Because of their blinding speed they can surprise birds in the air, disable them with a blow from their closed talon, and circle back to pick them up, often before they hit the ground.

You can browse through this video to see one take a Canada goose!! Gyrfalcon and goose

They are polymorphic – exhibiting different color phases – white, gray, and a dark, almost black. It breeds along the arctic coast and islands of northern North America, Europe, and Asia. The genus – Falco, comes from the Latin term for sickle – referring to the talons (claws) and rusticolus – the Latin ruis – country, and colere – to dwell, so a country-side dweller. The gyr – of the common name appears to be a German reference to vulture, a large bird, or from the Latin gyrus, or curved path, possibly a reference to the circling of the bird as it hunts for prey. Who knows for sure?

They are quite versatile hunters and will prey upon ptarmigan (which can make up to 90% of their diet), ground squirrels, artic hare, lemmings, and voles – basically anything that moves in the artic. They nest on tall cliff faces and may take over an abandoned golden eagle or raven nest, or just scape out a spot on the bare ledge. Males will occupy the nest area first – earlier than other raptors and thus beating the competition to food resources. Females will wait a bit before showing up at the nest, possibly so not to compete with the male for limited food supply early in the breeding season.

They will move south into the northern US during the winter and I recently noticed on the Tweeters – the bird siting site – that one was seen along the Skagit-Whatcom County line in the Samish Flats – always a good winter raptor area. Tweeters

Nest sites may be moved from one location to the next over the years, which may be based on success of the previous year’s nest, but will always be located in the middle of a cliff face from 30 to 90 ft. high. Even in areas of good habitat gyrfalcons are found at low densities – possibly reflecting a low tolerance of other breeding pairs. For instance – within Denali National Park, which is just over 2,000 square miles in area, there are only about 5 breeding pairs of gyrfalcons.

Males will initiate courtship with rapid flybys of the eyrie (nest site) in a figure eight pattern, screeching while he passes by the female. Males will also display during a complex pattern of flight rolls, steep climbs and dives, and rocking back and forth – all to show off his aerodynamic capabilities.

Gyrfalcons do not usually mate until they are 4 years old and will support a clutch of 2-5 eggs but only 2-3 typically survive to fledge from the nest. Fledging occurs in 45-50 days and requires quite the investment of energy by both parents to hunt enough prey to successfully produce a brood.

This bird is prized by falconers because of size, speed, and striking color. It has a long history of being used for hunting, going back to 12 AD in China but also popular with royals of Europe, North Africa, and Asia.

I’ve been lucky enough to see a gyrfalcon – once. I was working on a project at Port Clarence, about 75 miles northwest of Nome, AK with some additional work on Sitnasuak Native Corporation land just outside of Nome.

We had an off day and rented a beat up Ford Explorer with no back seat and a cracked windshield to go see what was out and about on the tundra. It was early October before we got out there for the field work due to some contract delay, but we did manage to find several herds of muskox.

On the way back to town we were following the route of the Iditarod, which is marked for the mushers by wooden poles across the bare tundra. We found a white phase gyrfalcon sitting on a pole. It was the only bird we saw all day. I’m not sure why he was spending the waning days of autumn up here but we were glad we got a look. We flew home the next day and the day after that winter started in earnest with a large snow storm.