Under a spreading chestnut tree

The village smithy stands;

The smith, a might man is he,

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles of his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands

——The Village Blacksmith, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1912.

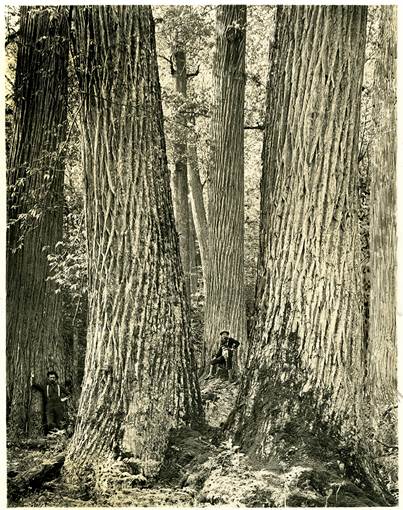

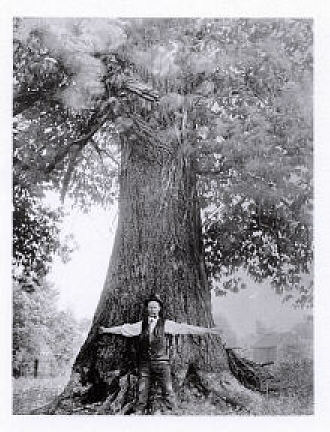

The American chestnut was once a widely distributed, magnificently large deciduous tree of the northeastern U.S. and down through the Appalachians. Historically the chestnut reached heights of 90 ft. and upward with a diameter of almost 10 feet. But a fungus, the chestnut blight, was introduced to the U.S. from Asia in 1904, first detected in 1904 at the New York Zoological Park (now the Bronx Zoo). It was downhill fast after that. The fungus travelled an estimated 50 miles a year and the disaster was hastened by salvage logging. Thinking that they might stop the advance and also harvest merchantable timber – large areas were clear-cut. But likely this also removed specimens that might have displayed some level of resistance. Within 50 years the blight decimated the entire population of American chestnut.

he blight quickly spread across the U.S. and now is extremely rare to find a specimen in its normal range that grows beyond 20 ft. high and larger than a diameter of 1 inch. The most common occurrence now is from sapling stump sprouts with taller ones that have died alongside younger ones sprouting. The number of trees that remain in its native range with a diameter greater than 24 inches is thought to be less than 100. Needless to say, these specimens are quite important for breeding purposes. A number of trees were planting outside its native range before the blight arrived and thus offer a source of unaffected trees.

The leaves are 5 – 8 inches long and are oblong/lanceolate, with sharp teeth on the sides. Castanea– from the Greek kastanea for chestnut and dentata – toothed, referring to the leaves. Chestnuts are monoecious (one house) where a tree carries both male and female flowers. Alas, sexual reproduction does not occur in the wild now because trees never reach this older stage. Small, pale green male flowers are located on 6-8 inch long catkins and the female flowers are found on the twig near the catkins. Trees cannot self-pollinate and thus need nearby companions. Nuts are produced in groups of three within a spiny green burr that is lined with a tannish velvet. Burrs fall to the ground and open near the first frost in the autumn.

The nuts were once economically important – sold on the streets during the Thanksgiving – Christmas holiday season (chestnuts roasting on an open fire…). They can be eaten raw or cooked. Native Americans harvested them for food and medicinal use such as treating whooping cough. The wood was valued for its straight grain and it was easy to split and saw. Because it contained tannins it was highly resistant to decay and favored for furniture, split-rail fencing, and general construction.

That such a large and common tree has been removed from the landscape is remarkable. In Pennsylvania it was estimated to comprise 25 -30% of the hardwood forest because of its rapid growth and prolific seed production.

Recent work in collaboration among the U.S. Forest Service, William and Mary College, and Purdue University inventoried chestnut trees in their range and found that of the estimated 71 million trees that only 16% of these trees had a stem diameter larger than 1 inch. So there a lot of small stump sprouts out there – none of which attain a size to be able to sexually produce.

“Historic populations of American chestnut have been estimated at 4.2 billion trees, so the findings could suggest that 10 percent of the population remains,” said Nelson. “First, we don’t know if the historic estimate included seedlings or only canopy trees. What’s clear from our findings is that today’s population is not only significantly smaller but spread over a wider range. Also, the size distribution is drastically different, with 84 percent of the present population in the seedling-size class.”

The American Chestnut Foundation is leading efforts to cross native resistant chestnuts with Asian chestnuts, and then back-cross pollinate these hybrids with American chestnuts. Offspring are inoculated with the chestnut blight fungus in plantations once they reach 1.5 inches in diameter. Two strains of the fungus are used – one weak and one strong, then those trees that display the highest form of resistance are left to grow and breed while the others are pulled from the plantation. Extensive genetic work has been done to help understand the genes that support resistance and provide guidance on the most advantageous cross-breeding.

But every backcross (with an American chestnut and a hybrid), although necessary to recover desirable American traits, also reintroduces the genes for blight susceptibility from the American parent. In order to remove those genes, the next steps at are intercrosses. In the first intercross, the most blight-resistant 15/16ths American trees are crossed with other blight-resistant 15/16ths American trees. Again, only resistant seedlings are saved. By 2020 the ACF expects to have a strong crop of American chestnut hybrids that have been thoroughly tested and ready for distribution. Wouldn’t that be something?

I grew up back east and went to undergraduate and graduate school there and was familiar with seeing stump sprouts around the typical oak-hickory deciduous forest. Up north of New York City is the small village of New Paltz, home of the Shawangunk Mountains and a mecca of rock climbing – so I would spend quite a bit of my time up there.

Once some friends and I, looking to kill time on a drizzly day, wandered into a estate sale on a farm and into the barn. We were chatting with one of the family members when my gaze wandered upward and – wow! There it was, running the 80 foot length of the barn – a massive chestnut beam. My mouth must have hung open for a bit and the older farmer said “yep – one chestnut beam – about 20 inches square”. These are cherished items and often salvaged from old barns for repurposing.

Well, that got the conversation going and he talked about his grandfather harvesting and milling the trees on the property, and building the house and the barn. When I’m old and creaky I hope to get back east and have the satisfaction of walking through a grove of chestnuts that are well on their way to this stature.