We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploringwill be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time. –T.S. Eliot.

This is a medium-sized tern that is circumpolar – breeding in the Arctic and sub-Arctic northern areas and then getting a second summer by migrating to the Antarctic coast following breeding. These birds display the farthest migratory flights of any bird. The have a length of 11-15 inches with a gray-white plumage and red/orange beak and feet. Their forehead is white and they have a contrasting black crown and nape with white cheeks. The tail is deeply forked and they have the typical swept-back look of the wings. They mainly eat fish and a range of invertebrates.

When I was recently in Iceland we saw then hunting in the tundra grass, presumably for insects as there are no native small mammals in Iceland. As with most terns they have a high wing aspect ratio — the ratio of wingspan to the mean of its chord (straight-line length of a wing profile), which translates into the ability to hover and more effortlessly fly long distances.

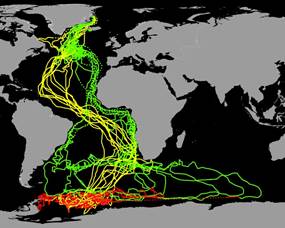

In recent studies of Arctic terns the average round-trip distance from Greenland/Iceland to the Weddell Sea in Antarctica and back again was 44,100 miles with a range of 37,000 to 50,700 miles. Since Artic terns can live for over 30 years the total distance flown in a tern’s lifetime can exceed three roundtrips to the moon. This recent Greenland study also noted that the birds had areas where they rested for up to 25 days at sea mid-way in the journey. The migration south for the winter took about 3 months, while the trip to northern breeding areas was completed in 40 days. These migration patterns correspond well with known seasonal variation of marine productivity and the concentration of Chlorophyll in the oceans, and thus the amount of algae and the organisms that feed upon them. Arctic terns migrate far offshore so your rarely see them from land except during breeding.

Breeding begins in the third or fourth year and Arctic terns mate for life, generally returning to the same colony each year. They have an elaborate courtship practices, especially for first time nesters. The courtship begins with a high-flight display where the female chases the male to a high altitude and then they slowly descend. Then come the “fish-fights” where the male offers fish to the female, followed by strutting around on the ground with raised tail and lowered wings. The whole display ends with the birds flying around and circling one another.

One to three eggs are laid and these terns are known for their aggressive defense of the nest, which can last for some time after you walk away from the area. They have a reputation for just not giving up. Both sexes take time incubating the eggs, which hatch in 25 days and the young fledge in another 24 days. Both parents also share in care and feeding of the hatchlings. Because they are ground nesters they are susceptible to ground predators. In Iceland this is limited to the arctic fox, but skuas and gulls also prey on eggs and young.

I recently saw these while in Iceland and they were the most common nesting bird we ran into on the tundra. Boy, are they loud and aggressive if you can anywhere near their nests, diving and swooping at your head and generally getting the point across that you were not wanted.