Once I spent a whole day there, a blade of grass in each hand to anchor me to the warm earth. I watched the sun rise, pass over my head and set. Ladybirds mated on my knuckle; a shrew nibbled a hole in my stocking while I tried not to laugh. Such a day was worth any punishment. – Emma Donoghue

Shrews are small, mice-like mammals in the Order Soricomprpha – they are not rodents (mice, squirrels, etc.) and do not have the continual growing incisors of that Order. They are typically very small, have a high metabolism, and a pointed looking nose with small eyes. And, other than the occasional mouse-in-the-house, small mammals are difficult to encounter unless you are really trying to find them, and this is especially so for shrews.

Sorex – Latin for shrew-mouse, cinereus – from the Latin cinis – ash-like.

Masked shrews are the most widely distributed shrew in North America and are found in Alaska, Canada, and the northern US extending down the Appalachians to Tennessee. In WA it is found at elevations from 2,300 to 6,000 ft., and is not found in the Puget Trough. It occurs in the Rockies south to New Mexico.

It is primarily associated with forests by can be found in arid grasslands, woodlands, and the tundra. Because it depends on a moist environment it is limited to areas with dense cover. There are about twelve subspecies identified, depending on what day you are talking to a particular taxonomist. Which is really quite incredible when you think about it – folks have studied this very small creature close enough to divide it taxonomically into a dozen separate boxes!

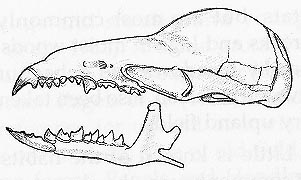

The masked shrew has dark grayish-brown fur on the back with a light gray-brownish color on the belly. Its fur is longer and denser in the winter. This shrew has a distinctly bicolored tail, dark above and pale below. Shews can be notoriously difficult to identify in the field and where the masked shrew overlaps in the SE with similar species the only way to clearly identify them is by skull characteristics – thus making it difficult, if not impossible to identify in the field.

These small creatures can be quite abundant and may dominate the small mammal population of particular habitats. They are often studied using pit fall traps, which can be made by duct tapping two large cans together vertically (cut top and bottom out of the upper one, leave the lower one with a bottom) and then burying them to ground level. Small mammals (or insects or amphibians) will plop into the cans while wandering around. Sometimes guide fences are put up to lead them towards the pit. In population studies using pit fall traps, masked shrews have made up 70% – 85% of the small mammals captured. Thus, from an ecological perspective they can be drivers of a number of natural processes.

Masked shrews will make use of other small mammal burrows or construct their own shallow burrows or runways beneath leafy cover or other debris. They are active all year including beneath the snow. Spherical nests two inches in diameter are constructed of leaves and grass and often located beneath logs, rocks, stumps, and other debris. In general, masked shrews are often associated with an abundance of downed woody debris, which provides cover and humidity.

These are very small animals – the adults total length (including tail) is 3 – 4 in. and adults weigh up to 0.23 oz. Their body temperature averages 101 F. They become sexually mature in 154 days and the gestation period is short – only 19 days, before up to six young are born. The young feed on solid food after 23 days and at birth weigh a slight 0.1 oz. Masked shrews will have two litters in a season, one in the spring and one in the fall. They pack a lot of activity within their short lifespan, estimated at a maximum of 1.8 yrs., but few survive more than a year. As with a number of small mammals, they are nocturnal and more active on cloudy nights – likely because the lack of moonlight reduces the chance of predation.

Masked shrews will eat three times their body weight each day because of their high metabolism. This is primarily a physics problem – as mammals get smaller their surface to volume ratio increases. As animals get larger their volume increases as a cubed function while surface area increases only as a squared function. When body size increases the surface are to volume decreases – thus, in proportion, small mammals have a very high surface area for their volume, which means their metabolism needs to be higher to keep up with the greater heat loss due to their proportionally large surface area.

In short – a beaver has an easier time keeping warm than a shrew that is 10x smaller.