I made the esperiment, found that they became perfectly soft by boiling, but had a very bitter taste, which was naucious to my palate, and I transferred them to the Indians who had eat them heartily— Meriwether Lewis, August 22nd, 1805

Bitterroot is a widespread plant throughout the arid western United States. Its range includes Washington and California eastward to Montana, Colorado, and Arizona. It is a perennial plant that grows on well-drained gravelly soils in dry shrublands, often dominated by sagebrush, but also in piñon-juniper woodlands, oak woods, and ponderosa pine or Douglas-fir forests. It is pretty hardy and can grow at elevations from 2,500 feet in California to over 10,000 feet in Utah. Early in spring, the succulent, fingerlike leaves elongate and after the leaves have withered, the deep pink to rose (or sometimes white) flowers emerge presenting a drop of color in an otherwise rather stark landscape. The flowers are up to 2 inches across.

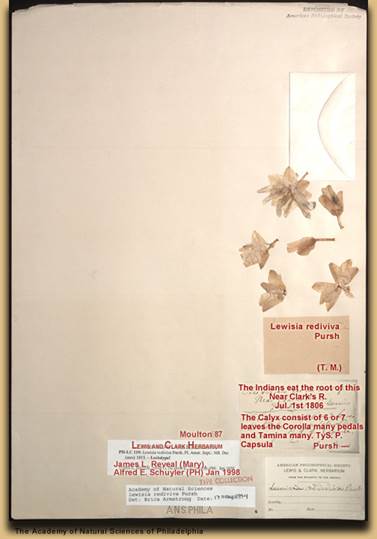

The phrase “Near Clark’s R. Jul. 1st 1806 Lewis”—written by Frederick Pursh—relates that Lewis collected the specimen on July 1, 1806 in the vicinity of Travelers’ Rest near the river that Lewis had named for his “worthy friend and fellow traveller Capt. Clark,” but is now called the Bitterroot River.

George Drouillard, a hunter and interpreter on the Lewis & Clark Expedition, had brought the plant to his attention after Drouillard had a run-in with some Shoshone who left him in possession of some of their belongings. The woven bags included dried roots of three species, one of which came to be called racine amer by the French trappers, meaning “bitter root”. Lewis collected whole plants near Travelers’ Rest Creek, and gave them to Frederick Pursh after returning to Philadelphia. Pursh described a new genus and named it Lewisii in honor of Lewis. When Lewis’s pressed, dried specimen was examined months later at the Philly Academy of Natural Sciences it showed signs of life so it was planted. When it grew the species was christened redviva, meaning “restored to life”.

…another species (sic) was much mutilated but appeared to be fibrous; the parts were brittle, hard, of the size of a small quill, cilndric (sic) and as white as snow throughout, except some small parts of the hard black rind which they had not separated (sic) in the preparation — Meriwether Lewis, August 22nd 1805.

Lewis later collected the plant near Traveler’s Rest along what is now the Bitterroot River upon his return trip in July 1806.Bitterroot is a culturally significant plant for several Native American tribes in the West (Flathead, Kutenai, Nez Perce, Paiute, Shoshoni and others). Traditionally, the roots were gathered, dried for storage, and used for food or trade.

The roots are harvested by using a digging stick, often made from the wood of the mock-orange. The top of the peeled root is split and a small orange-red structure called the “heart” (apparently the young, developing plant of the next year’s growth) is removed. Not every root has a “heart”, but when present it will make the root very bitter if it is not extracted – possibly Lewis’s mistake in sampling these. The peeled roots are washed and laid on mats or grass for two or three days to dry. Generally, the roots are stored in sacks, or sometimes stored after being dried, in pits lined with pine needles. Care was taken to pack them tightly to prevent air from circulating, because this would make them hard and dry.

Once I was out in sagebrush country with the Yakama Tribe ethnobotanist and we came across a patch of bitterroot. I asked if Tribal members eat these by pounding them into patties – she looked at me as if I had not yet learned anything important from my time on this earth – and it was if I had asked someone on July 4th if they ever take hamburger and make it into patties and cook it on the grill.

Bitter-roots, fresh or dried, are usually cooked by steaming or boiling or by pit-cooking for about half an hour. In the past, they were steamed in a birch-bark container using hot rocks. Some soaked then overnight and cooked them in soups, boiled together with saskatoon berries and deer fat, black tree lichen and fresh salmon eggs, tiger lily bulbs and ripened salmon eggs, dried gooseberries or other food combinations. They are seldom eaten dried, because they swell up in the stomach and cause discomfort. If stored alone they become very bitter, so are often mixed with dried gooseberries or dried saskatoons.

I’ve seen this little guy all over eastern WA, OR, ID, and MT. The above two photos are in eastern WA on May 14th in 2013; I suspect that this year they may be blooming a bit earlier due to the warmer spring to date. It seems like one day it’s late winter and then all of the sudden they just pop up all over the place in early spring and look a bit odd – a very colorful showy flower without any leaves, often in very dry and shallow soils.