he grass divides as with a comb,

A spotted shaft is seen;

And then it closes at your feet

And opens further on ——Emily Dickinson, The Snake

This is a common snake within its range, averaging 42-72 inches in length, with a diameter at the widest section of its body of 1.5 inches and typically weighing 1 – 5 lbs. It is a nonvenomous snake that is uniformly black except a white chin, has weakly keeled scales, and a divided anal scale. Hatchlings have a banded pattern that darkens with age, which is why the less knowledgeable often mistake the young rat snake for a copperhead, a venomous species. But rat snakes have round pupils instead of copperheads’ vertical pupils, have narrower heads, and lack the pit sensors of copperheads and rattlesnakes.

When handling an adult rat snake you can tilt its body around and see the hard to distinguish bands in the changing light angle. The longest one on record was 8 ft 2 inches, which makes it the longest snake in North America. It’s interesting to note that while there are a number or large temperate snakes, there are no large temperate lizards. It’s not clear why this is so – some suggest that snakes can more easily thermo-regulate in a temperate climate while concealing themselves, in rock cracks for instance, whereas larger lizards would be more susceptible to predation.

The black rat snake is widely distributed with a range from New England south through Georgia and west across the northern parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, and north through Oklahoma to southern Wisconsin. An isolated population inhabits southern Canada and northern New York. They can be found from sea level to the higher elevations throughout the Appalachians Mountains.

Rat snakes, as you can guess from their name, are primarily known for preying upon rodents, but adults also eat birds, nestlings, and eggs. Juveniles may eat small lizards or frogs. Rat snakes are constrictors and kill their prey by wrapping coils of their body around the animal and suffocating them. They then eat their prey whole.

They are excellent climbers and will get into trees and structures to eat nestlings and eggs. When working in PA/MD I assisted on a bluebird box project, cleaning and monitoring the next boxes. Each spring one of the tasks was to grease the support poles leading to the boxes to deter the rat snakes from raiding the nest.

Dr. Harry Green, in his wonderful book – Snakes – recalls an extended article in Bird Watchers Digest that recounted the mission of a black rat snake to raid a house wren nest on the porch of a PA farmhouse. The snake had to negotiate almost insurmountable eaves and gutters before cleaning out the nest. A number of letters from the bird advocates criticized the article but the author concluded that “…in the case of the nestlings and the snake, respecting the intricate web of life forced us to applaud the winner even though we had been rooting for the losers.”

The classification of this species has bounced around a bit since 2002 when it was still named Elaphe obsoleta – and, ok, I really wasn’t aware of the changes until new nomenclature until just this week! But in defense I think the last time I handled one was in 2010 or so. Apparently a series of genetic studies has made the lineage clearer. And because Pantherophis is masculine the species name becomes obsoletus. Though the discussion is not over among taxonomists – some consider the eastern variety to be a distinctive subspecies – but let’s just stick to this scientific and common name for now. Other common names include white-chinned racer, chicken snake, Allegheny black snake, and one I’ve heard – black pilot snake. Pantherophis – from the Greek pan for bread, referring to the loaf-like profile;thero – wild beast of summer; and aphis – snake. Obsoletus – old, worn out or low – which may just refer to it being “common”.

Mating occurs in May through early June. The male will wrap its tail around the female while aligning their vents. The male will insert his hemipenis into the female cloaca – mating may last from a few minutes to a few hours. I once came across a pair of mating black rat snakes while climbing up to the Appalachian Trail on the ridge behind my house in Maryland – just across the river from Harper’s Ferry WV. They were lying among the boulders and it took me a minute to figure out what exactly was going on. I left them alone and on my return trip and hour later they were nowhere to be found. Five weeks after mating the female will lay about 12-20 eggs, which hatch in 65-70 days.

Rat snakes are preyed upon by a number of animals while juveniles, and less so when adults. Humans, who seem to have an unreasonable fear of snakes, don’t take lightly to this large black critter. Mink, owls, and hawks will eat rat snakes though there are reports where the snake has turned the tables and killed even large raptors such as a red-tailed hawk.

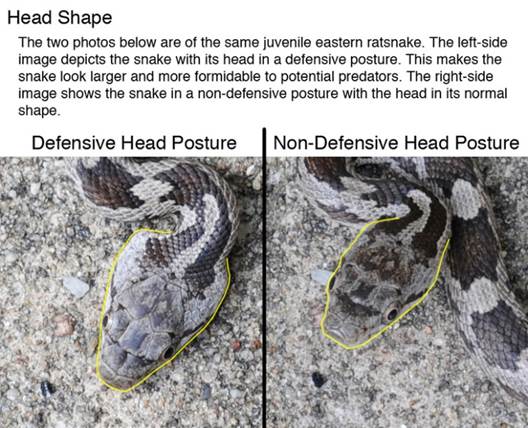

When cornered these snakes will kink up their body or make coils and will strike. They also will shake their tail, feigning a rattlesnake, which can be intimidating if you don’t know better. They also flatten and widen their head to look more intimidating. As with nonvenomous snakes they have a series of fine, backward pointing teeth on the upper and lower jaw that aid in pushing prey down their gullet. But this also results in a rasping bite when you try to pick them up and are off the mark. The inevitable reaction to a bite is to pull back, which makes for a nice series of scratches. A good method is to distract with one hand and quickly snatch with the other. Once in hand though, rat snakes calm down quite nicely – unless they don’t. And if they are a bit too excited a first they will expel a (to most) foul smelling dark musky liquid – whose aroma stays on your hands for some time. It reminds me of, well, snakes – so I don’t mind the mishap so much.

I took the photo of this one in front of my house in MD. I had picked him up off the road while I was out for a long run along the rural farm roads as I had been keeping an eye out for one because a friend wanted one for a pet. But I came across him about three miles from home, so ran back home with him wrapped around my forearm – he was about 5.5 ft long. Once home I put him in a five gallon pickle jar with some slits in the plastic top for air and placed a brick on top so he couldn’t pop the lid, and placed it all in a corner of the house.

After I ran a few errands I came home to an undisturbed but empty container. Somehow he maneuvered himself through one of the lid slits and moved the brick just enough to squeeze through. After two hours of searching the house I gave up. It was a refurbished 1780’s house that had a less-than-airtight structure, so he likely made his way through the walls, up to the attic, and then outside. I did go up to the small attic to look the next day and found about 20 shed snake skins, not from him, but maybe his relatives.