Fish gotta swim and bird gotta fly; insects, it seems, gotta do one horrible thing after another. –Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek.

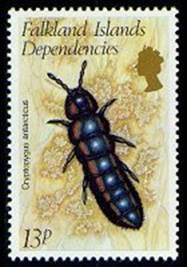

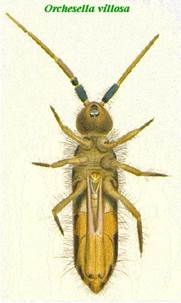

These are among the most common invertebrates in the environment but are rather inconspicuous because of their size. They are about 1/16th to 1/8th inch long, have three pairs of legs, a moderately long and segmented antennae and are mostly slender and elongated, though there are some that are stouter. Springtails can be dark brown, grey, or black though some are white with a slight iridescence. These once were lumped in the Class Insecta (Insects) but is now a separate subclass under the Hexapoda subphylum. Thus, you can’t call them an insect without risking the wrath of your etymologist friends. There is still some dispute as to the Class that springtails are within, but let’s not go there.

| -Compound eyes absent or reduced to a cluster of not more than 8 ommatidia -Antennae 4- to 6-segmented -Abdomen 6-segmented -Ventral tube (collophore) (4) present on first abdominal segment | -Tenaculum located ventrally on third abdominal segment -Furcula (springtail) (6) attached ventrally to fourth abdominal segment -Genital opening on fifth abdominal segment -Body frequently clothed with scales |

Collembola – Greek coll – meaning glue embol – meaning wedge – which refers to a peg-shaped structure, the collophore, on the underside of the first segment. The collophore was once thought to have an adhesive function but is involved in water transport and excretion. There are at least 6,000 species of Collembola and possibly as many as an estimated 50,000.

Springtails are wingless and do not fly but they can bounce around quite well, as indicated by their name. They have a specialized forked appendage called a furcula, which is located beneath the abdomen. When it is not in use it’s tucked under the body and is set with tension – when disturbed the springtail releases it and it hinges downward quickly, flinging the organism quickly upward. When they “spring” they can bounce up to 8 inches or so – 10-50 times their body length.

Springtails are found in damp conditions and in organic debris – in the soil, leaf litter, under bark, decaying plant matter, rotting wood, etc. They are omnivorous and feed on fungi pollen, algae, and general organic matter. Sometimes you can find them in the soil of house plants. They have biting mouth parts that are mostly retracted into their head. One species Hypogastruna nivicola, can be found active on snow in the winter, thus its common name – snow flea.

Collembola do not have a tracheal respiration system, which means they breathe through a porous cuticle, or skin (of sorts). These are rather primitive organisms that can be traced to the early Devonian – fossils have been found from 400 million years ago. Fossils of them are rather rare and most of the preserved records are from Collembola encased in amber.

Springtails are thought to be among the most abundant of macroscopic animals with an estimated density of up to 100,000 individuals per square meter of ground. Because they respire through their “skin’ they are very prone to desiccation and will not be found in dry regimes. Some species are known agricultural pests but they play a strong ecological role by carrying spores of mycorrhizal fungi and mycorrhiza-helper bacteria on their tegument that are important for plant-fungal symbiosis.

Mating occurs as the female lays down a pheromone (scent) causing the male to deposit a stalked spermatophore (sperm sack) on the ground, which the female then picks up. The thin stalk keeps the spermatophore off the soil. Some species appear to lay down a spermatophore when they feel like it without female urging. In other species competing males will eat each other’s spermatophores to keep them from successfully reproducing. A female will lay 90-150 eggs during her life, which varies by species. The eggs take about a month to hatch at 50 degrees but quicker at warmer temperatures. They are thought to live about a year and will be sexually mature after 3-13 moults – which occur every three days or so.

I regularly see springtails in my worm bin in my back yard where we bury our vegetable waste. They seem to be most abundant in the spring when it’s a bit warmer, though this could be a function of me not wanting to search around during the dark and wet winter. I did search through a few potted plants in the office this morning without success. If you sift through some moist soil in the palm of your hand there is a pretty good chance you can see the springing up a couple inches or so as you disturb them. Quite an abundant and interesting critter.