Giant green anemones are found along the west coast of North and Central America from Alaska south to Panama. They also occur in Hudson Bay Canada and the east coast of Russia. They are found in the intertidal and lower reaches of the subtidal zone (up to 40 feet deep) in cold water and typically in relative high energy wave zones. They do best in waters that range from 50-70° F. They often are found within or near mussel beds, one of their main food sources.

Anemones are in the phylum Cnidaria – a extremely diverse group of aquatic invertebrates that includes corals/anemones, box jellies, fire corals/hydroids, and true jellyfish. The Greek Cnidos – referring to stinging nettle – more on that later.

They also all have a free swimming medusa phase (that looks like a tiny jellyfish) and a sessile polyp phase. In case you were not sure – anemones are animals and not plants, though they do resemble an odd underwater variety of plant with their flowing tentacles. They have tube like columnar bodies that attach at the bottom to a hard substrate such as rock or pilings. The column can be up to 12 in tall and at the top is a round cap with a crown of numerous tentacles.

The crown has at least 6 rings of tentacles. The exhibit radial symmetry. So if you are looking down at them from the top, if you divided them in half from top to bottom, it would not matter where you placed the plane of bisection – each side would always match the other half. Once attached to the substrate, they typically do not move, but if conditions do not turn out to be favorable they can use their “foot” to move along to a new location.

Algae grow in the anemone’s tissues in a symbiotic (mutually beneficial) relationship – the more sunlight available the greener the anemone due to the growth of algae. Anemones become sexually mature at 5-10 years and spawn by releasing eggs and sperm into the open water for diffuse mixing. You cannot tell a male from a female by just looking at it – that requires dissection –or being at the right time and place during spawning I suppose.

About 3 hours after fertilization the egg begins to divide and continues to a larvae stage where they swim or float (medusa stage), often dispersing a wide distance. During this stage they will eat zooplankton (small animals), phytoplankton (small plants), and even other larvae. They feed by secreting a mucus thread that food particles adhere to and then are drawn to their mouth. After three weeks the larvae settles down to an area of suitable substrate, develop their pedal disc and complete the metamorphosis to an adult form.

Not much is known about their life span though one was kept alive in an aquarium for, yes, 80 years! It’s thought that in the wild they can live for about 150 years.

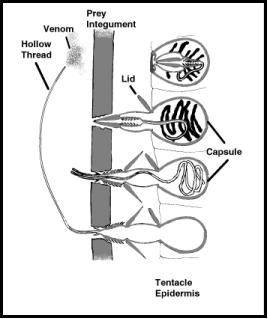

They are carnivores and will eat quite a variety of food including sea urchins, mussels, crabs, and small fish. Once a prey item is detected an anemone stretches its tentacles and paralyzes its prey using the nematocysts. Nematocysts are a very intriguing weapon found in a Cnidarians. Some organisms, such as clownfish (remember Finding Nemo?) have evolved a relationship with anemones and a tolerance to stings.

They are toxin organelles that are spring-ready. When stimulated they quickly fire into the target and imbed with an array of barbed hooks and implant their toxin. This is a common weapon/defense strategy for a number of invertebrates such as hydras, corrals, and most commonly known, jellyfish.Here are a couple photos of green anemones near a mussel bed at low tide and one of the general habitat type – rocky tide pools along the Olympic National Park coastline.

I was on a several day backpack trip here with Connie and we were investigating the tide pools. We ended up talking about the anemones and Connie, always well informed, told me that you can touch anemones because they have a relatively mild toxin in their nematocysts and your fingers are just not sensitive enough to feel it.

But, she went on, that if you find an anemone that is just covered by water so it tentacles are extended you can lightly touch it with you tongue and, because it is more sensitive, you will get a slight sense of tingling or an acid taste. Ever the inquisitive naturalist – sure why not? So I bent over and found an appropriate subject and did as requested.

Shortly after as we resumed hiking my tongue just got more and more tingly and then numb until I felt like I had gone to a not-so-precise dentist and was now slurring my consonants. Connie was just laughing saying “You were supposed to just touch it with your tongue, not French kiss it!” Sigh. After about 40 minutes or so all was back to normal.

These are wonderful and quite lovely creatures that you can easily find on the Oregon and Washington coasts. Just go easy on the amorous greetings.